sam durant in conversation

with adjunct curator pedro alonzo

San Cristóbal de las Casas, 1992, presented in Cass Corridor, Detroit, MI. Photo by Darryl Deangelo Terrell. Photo courtesy of the artist and Library Street Collective.

Recently, Peter Doroshenko mentioned that he had been thinking a lot about your work. My response was, “how can you not be thinking about Sam's work”? Many of the topics of your practice such as mass incarceration, racial inequality, history of protesting and iconoclasm have taken center stage in the national dialogue. Does it feel like society is catching up to your work?

I always hope my work is relevant, but I agree with you that there are times when it is more obvious, now is certainly one of those times. I’ve been working with monuments and memory and the history of racial and social justice struggles for a couple of decades and both of these issues are front and center of the discourse these days.

Labyrinth, a 40 x 40 foot chain-link fence maze is currently on view at the Contemporary Art Center in Copenhagen. It was originally shown in the heart of Philadelphia, across from City Hall, as a means to bring attention to mass incarceration. The public was invited to hang statements on the structure that responded to the issue. Still today, the USA has the world’s largest prison population. How does Labyrinth read in Denmark, a country with harsh immigration policies? And how does it reflect back on the USA with the immigrant families separated and children often held in “Detention Centers” on the border?

I just returned from Copenhagen where I met with the group who have been organizing and running the programing for the Labyrinth participatory program. They have slightly altered the focus for the context in Denmark. Some emphasis is on the COVID-19 crisis and how it affects different people and different groups of people while a lot of emphasis has been toward the different immigrant communities, including the fraught relationship to Indigenous Greenlanders. Denmark also has a history of operating slave plantations in the Caribbean and slave trading on the African coast in the 19th century. So, in addition to the questions about criminal justice and incarceration, there is quite a broad reach in the programing for Labyrinth in Copenhagen. It was very moving to see all of the contributions, as it was when we did it in Philadelphia. I would not have imagined so many parallels between the locations. I met with three extraordinary individuals, two men and a woman who were in the process of moving from prison back into society. I will always remember the guys at Graterford, how impressive they were, how moving their stories were as they dealt with their crimes and transformed themselves through art. It was a similar experience in Copenhagen.

The Meeting House, 2016 dealt with the legality of slavery in Concord, Massachusetts. Among other things, the work revealed the early development of often veiled and systemic forms of racism in the North as opposed to the explicit forms of racism that have characterized the South. At a moment of awakening among many whites in this country aspects of institutional racism are becoming evident. You clearly stated that whites were the intended audience for this work. Can you share your own process of awakening and the importance and challenges of confronting white Americans with these issues?

That’s a great question and one that is extremely complex, so full of challenges. I believe I became aware of racial identity and racism because of the socio-political environment I grew up with, in the late 1960s and ‘70s. It’s worth remembering that whites have always been involved in the civil rights struggle, from John Brown to Freedom Summer. Not forgetting, of course, that the movement was led by African Americans, as John Lewis’ recent passing reminds us.

An early memory for me was the first Native American protest against Thanksgiving at the Plymouth Rock in 1972, I believe. That really opened my eyes. As a little white boy it hadn’t occurred to me that the arrival of English people back in the 17th century was a catastrophe for the Native Americans. Around this time the Boston public school system was taken over by the federal courts in an attempt to desegregate one of the country’s most segregated school systems. I was in a program called “Metropathways”. It was an art and social studies oriented nomadic public high school where kids from all over came the Boston area came together to study with some very radical teachers.

Identity has been a highly charged issue for the last ten plus years. Unfortunately, it often is debated on social media, which is the absolute worst place to have any conversation, let alone one as complicated as the issue of race. Add in the degree of polarization across US society makes it is almost impossible. But I hold out hope for us to join together across identitarian borders to fight racism and injustice. I follow Martin Luther King and James Baldwin’s lifelong call for whites to join the African American struggle to abolish white supremacy. Obviously, I am aware of my standing as a white male with all the unearned privileges. So, I always want to be sure that my work reflects my identity- that it comes from my subject position. I have never claimed to speak for another, or from another’s perspective or experience. This must always be clear. At the same time, we have to recognize that in America we are all bound together through our history, white people have tried to ignore that and some non-whites as well. Our stories are interconnected. I am not a nationalist of any sort, so I feel no need to deny this interconnection and interdependence. Quite the contrary I want to celebrate that, to promote coming together. A sculptural work that came out of the experience of The Meeting House called Transcendental (Wheatley’s Desk, Emerson’s Chair), 2016 is an example of trying to represent this idea of interconnection. The work proposes that without the (first published African American poet) Phillis Wheatley there would not be Ralph Waldo Emerson. And to push further, I believe Emerson stands on Wheatley’s shoulders, even if he would never have believed that. Some might even theorize the idea is that everything that whites have accomplished in the U.S. is owed to African America and Native America. I love that Toni Morrison line, “deep within the word “American” is its association with race.”

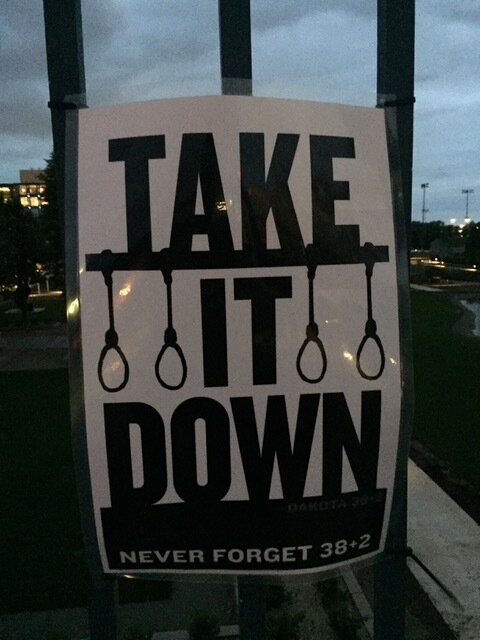

The Meeting House was a multifaceted project that was composed of a pavilion, interventions in the historic Old Manse (the ancestral home of Ralf Waldo Emerson), events and signage. It was the signs that were placed across the property that referred to historical elements of the site that were the most provocative. One in particular, (see below) drove people crazy. Can you talk about developing the signs?

Land conservation while environmentally beneficial, has served to keep property values high in Concord. A significant effect of this has been the ongoing deterrence if a more racially integrated community. Today Concord has about the same percentage of African American residents as it did in the 1770s. More than one-third of them are in the Concord Prison.

At some point in the planning of the project, it seemed important to have some prompts for visitors to the site. As my practice usually involves a lot of research, of course there was so much material that made sense to incorporate into thought-provoking messages. It’s important to note that much of the framing for this aspect of the project came from historian Elise Lemire’s remarkable book “Black Walden”.

People in Massachusetts are always proud of the fact that Massachusetts was the first start to abolish slavery in 1783. However, they always forget that Massachusetts was also the first colony to legalize slavery in 1641. One of the key elements of The Meeting House were the public events called Lyceums that functioned as a platform for dialogue around the complicated legacy of slavery. Can you share your thoughts on the Lyceums and the importance of public discussions?

When we did the project in Concord we got some push back from that community, they did not like to be confronted with either historical racism or its deeply institutionalized present-day manifestation. We began conceptualizing The Meeting House soon after Michael Brown’s murder in Ferguson, a tragedy that really changed the paradigm. Because of real-time witnessing, the internet and cell phone cameras, white people could no longer ignore the murders of black people. I was very influenced by Tim Phillips’s work with his org Beyond Conflict and the desire to build bridges and resolve deep and oftentimes violent conflicts. His approach is through discussion, bringing both sides together to be in proximity to each other, to hear each other’s stories in person. Through research, we learned about the history of the Lyceum and its roots in the abolitionist movement. It seemed like a great time to revive that tradition.

From September through November of 2019 the exhibition Iconoclasm was presented in Detroit. The exhibition consisted of large drawings that depicted the destruction of monuments and statues throughout history and across the globe. As a means to demonstrate the fragility of our symbols, several of the drawings were hung outdoors. One was stolen. Can you share your thoughts on the often-violent removal of symbols and statues?

In 2008 I started an online archive cataloging the defacement and destruction of public sculptures and monuments for an exhibition in The Hague. It was within this long-term engagement with iconoclasm and public symbols that I began the series of Iconoclasm drawings. They also became part of working through the controversy over my public sculpture Scaffold (2012). While aware that my work could be provocative, I was unprepared for the protests that erupted at the Minneapolis Sculpture Garden in 2017. In the months that followed the events in Minneapolis, I sought a deeper understanding of how representations evoke such strong emotions. I participated in many discussions, public and private, listening to others and testing my own theories as I tried to expand my understanding of what happened at the Walker Art Center. I consulted texts devoted to documenting and understanding the history of iconoclasm. Art historian David Freedberg’s work helped me to appreciate the powerful, often unconscious energy that can burst forth when a viewer is confronted with images that disturb beliefs, challenge world views, or trigger traumatic experiences. We are seeing those impulses acted on around the world today as people who have been traumatized and whose dignity has been assaulted take down symbols of their oppression.

We have worked together a great deal since 2015. Our projects have never been easy but it has always been a pleasure to work with you. Your projects address complicated topics including criminal justice and the legacy of slavery and although there has been opposition and people who did not like the artworks, particularly in Concord, we never had violent blowback. Your projects were always tolerated and we were able to have discussions with those who were unhappy. Can you discuss what went wrong in Minneapolis that led to the removal of Scaffold, 2012 at the Walker Art Center?

There is definitely not enough time or space to answer that question here! It is an extremely complex question, but to be as brief as possible it was at best, a failure of outreach on the part of the Walker Art Center. They failed to understand that one of the images in the work, the image of the Mankato Gallows, would be problematic to the large Dakota population in the city of Minneapolis. Normally museums must prepare and educate the viewers about the work they exhibit. They should know about their communities and be in dialog with them, the Walker was not, and did not do that with the Dakota. When the work was being installed in the sculpture garden, members of the Dakota recognized the Makato gallows image in the work and began a vociferous and effective protest. They had no information about the work’s intention. They had not been consulted before installation. It was an extremely big mistake and resulted in one of the most controversial and complicated issues in public art and its relation to its site.

San Cristóbal de las Casas, 1992, 2018, Graphite on paper. Drawing in collaboration with Milenko Prvački. Photo by Joshua White. Photo courtesy of the artist and Library Street Collective.

Exterior, facing Old Manse, Sam Durant, The Meeting House 2016, Photo by Alex Jones, Courtesy of The Trustees.

The Meeting House, seen from interpretive sign, Sam Durant, The Meeting House 2016, Photo by Alex Jones 2016, Courtesy of The Trustees.

Labyrinth (2015). Installation view at Copenhagen Contemporary, 2020. Courtesy Sadie Coles HQ, London; Blum & Poe, Los Angeles, Paula Cooper Gallery, New York and the artist. Photo: David Stjernholm.

Scaffold, 2012. Installation view at Minneapolis Sculpture Garden/Walker Art Center.

Durham, 2018, presented in Cass Corridor, Detroit, MI. Photo by Darryl Deangelo Terrell. Photo courtesy of the artist and Library Street Collective.

Durham 2018, 2018, Graphite on paper. Photo by Joshua White. Photo courtesy of the artist and Library Street Collective.

Lyceum, Sam Durant, The Meeting House 2016, Photos by Above Summit, Courtesy of The Trustees.

Lyceum, Sam Durant, The Meeting House 2016, Photos by Above Summit, Courtesy of The Trustees.

Labyrinth (2015). Installation view at Copenhagen Contemporary, 2020. Courtesy Sadie Coles HQ, London; Blum & Poe, Los Angeles, Paula Cooper Gallery, New York and the artist. Photo: David Stjernholm.

Protest sign at Minneapolis Sculpture Garden.

about sam durant

Sam Durant, born in 1961, is an interdisciplinary artist whose works engage a variety of social, political, and cultural issues. Growing up near Boston in the 1970s he experienced the radical pedagogy of A.S. Neill, Maria Montessori, and John Holt, along with anti-war demonstrations and the desegregation of the public-school system. Exposure to an educational culture emphasizing democratic ideals, racial equality, and social justice created the framework for Durant’s artistic perspective. Often taking up forgotten events from the past, his work makes connections with ongoing social and cultural issues.

Durant’s interest in monuments and memorials began with Proposal for Monument at Altamont Raceway, Tracy, California, 1999, referencing the violent end to the infamous free concert and arguably to an era; and continued notably with Proposal for White and Indian Dead Monument Transpositions, 2005, re-contextualizing memorials to victims of the conquest of North America; and more recently with Proposal for Public Fountain, 2015, a marble work depicting an anarchist statue being blasted by a police water canon. Earlier works excavated subjects as diverse as the repressive practices of Modernism, the death drive of 1960s and 1970s pop music, and artist Robert Smithson’s theories of entropy. Contemporary examples of his oeuvre encompass subjects such as Italian anarchism, cartographic histories of capitalism, gestures of everyday refusal, and the meaning of museums for their visitors. Recent major public art projects include Labyrinth, 2015, in Philadelphia, addressing mass incarceration; and The Meeting House, 2016, in Concord, Massachusetts, focusing on the subject of race in colonial and contemporary New England.

In 2007, Durant compiled and edited the monograph Black Panther: The Revolutionary Art of Emory Douglas, and curated the eponymous exhibition at Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, and the New Museum, New York. From 2005-10, he was a member of the collective Transforma Projects, a grassroots cultural rebuilding initiative in New Orleans. In 2012-13, Durant was an artist-in-residence at the Getty Museum, Los Angeles, where he collaborated with the education department to produce a discursive social media project called What #isamuseum? This became a solo exhibition in 2016 at University of California, Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive, Berkeley.

Durant’s work has been included in numerous international exhibitions including the Busan Biennale, South Korea; Liverpool Biennale, United Kingdom; Sydney Biennale, Australia; Venice Biennale, Italy; Whitney of American Art, New York, Biennials (2006, 2014, 2008, 2008, 2007, 2004, respectively); documenta 13, Kassel, Germany, 2012; Yokohama Triennale, Japan, 2017; and Power to the People: Political Art Now, Schirn Kunsthalle, Frankfurt, Germany, 2018; and Forgetting–Why We Don’t Remember Everything, Historisches, Museum, Frankfurt, Germany, 2019.